Narrowing the Partisan Divide

About two-thirds of U.S. adults would want their child to attend a four-year university if they had a child of college-going age, but significant variations exist based on income, educational attainment and partisan affiliation, according to new polling released today.

Support for a child attending a university to earn a four-year degree was substantially higher among Democrats than it was for Republicans, according to a survey being released today by the opinion and research journal Education Next. But the gap narrowed if the partisans were given more information, to the point where it disappeared if survey respondents were given information on both the cost of college and the likely lifetime earnings benefits of a four-year degree. That information made Republicans more likely to want a university education for a child than they had been previously — but it had the opposite effect on Democrats.

The findings come on the heels of an eye-opening survey released by the Pew Research Center in June that showed Republicans’ view of higher education has deteriorated significantly in recent years. The new survey would seem to point to significant nuance in partisans’ views of higher education, indicating that positions can change based on information available and that broad perceptions do not necessarily translate into personal preferences.

Pollsters working for Education Next asked 4,214 adults over the age of 18 a series of questions between May 5 and June 7 of this year. The questions addressed issues ranging from charter schools to immigration policies in addition to higher education.

Where Would You Want to Send Your Child?

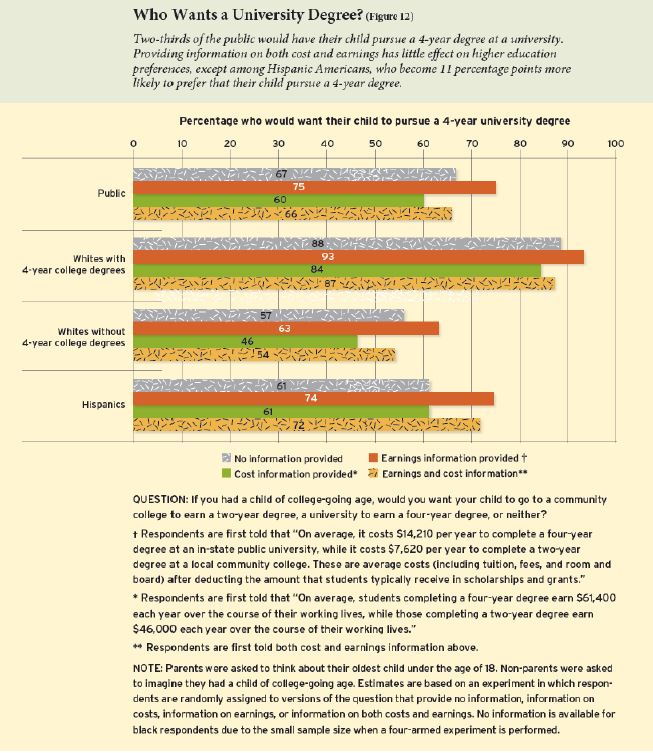

Different groups were asked variations on a question about whether they would want their child to attend a university to earn a four-year degree, a community college to earn a two-year degree or neither. The first group was simply asked which option they would want for their oldest child under the age of 18 or if they had a child of college-going age.

Just over two-thirds of all respondents, 67 percent, said they would want their child to attend a university to earn a four-year degree. About a fifth, 22 percent, said they would want their child to attend community college and to go on to earn a two-year degree.

When the findings were broken down by partisan affiliation and leaning, significant differences emerged. Desire for a child to attend a four-year college was substantially lower for Republicans and higher for Democrats. The opposite was true when it came to two-year colleges.

Just 57 percent of Republicans said they would want their child to attend a university for a four-year degree, compared to 75 percent of Democrats. But 31 percent of Republicans said they would want their child to attend a community college for a two-year degree, compared to 16 percent of Democrats.

A second respondent group was asked a question that included information on the earnings benefits of a four-year degree. It noted that on average, students completing four-year degrees earned $61,400 each year over the course of their working lives, while those completing two-year degrees earned $46,000 annually on average. In responses, interest in a child pursuing a four-year degree rose among all respondents, as well as both Republicans and Democrats. About 75 percent of all respondents, 70 percent of Republicans and 79 percent of Democrats picked a four-year degree for their children.

A third group was asked the question after being told only about the cost of higher education. Respondents were told a four-year degree costs $14,210 per year at an in-state public university on average and that it costs $7,620 per year at a local community college to complete a two-year degree. Interest in a four-year degree fell and interest in a two-year degree rose among Democrats. Interestingly, interest in a four-year degree was still higher among Republicans than it was if they were given no information, while interest in a two-year degree was slightly lower.

When given only information on the cost of college, 60 percent of all respondents said they would want their child to pursue a four-year degree, and 26 percent said they would want their child to pursue a two-year degree. Among Democrats, 63 percent picked a four-year degree and 26 percent picked a two-year degree. Among Republicans, 60 percent picked a four-year degree and 27 percent picked a two-year degree.

It should be little surprise that adding information to a question will change respondents’ answers. The results of such “priming” are a well-known phenomenon among those who construct surveys. However, comparing the way different groups react to different information can be insightful.

Consequently, the survey’s most notable result came from a group of respondents that was given information on both the costs and financial benefits of higher education. When they were given the average annual earnings of a student with a two- or four-year degree and the average annual costs associated with those degrees, respondents’ answers mirrored those who were given no additional information.

Two-thirds, 66 percent, of all respondents said they would want their child to go to a university for a four-year degree — virtually identical to the rate of respondents who were given no information. About a fifth, 22 percent, picked a two-year community college, also identical.

But the breakdown between Democrats and Republicans changed significantly. When cost and earnings information was presented, 66 percent of Republicans and 66 percent of Democrats chose a four-year university as the desired destination for their child. That’s up nine percentage points among Republicans and down nine percentage points among Democrats from those who were given no information. Another 24 percent of Republicans and 19 percent of Democrats chose a community college, down seven percentage points among Republicans and up three percentage points among Democrats from those who were given no information.

“When we provide information on the costs and benefits of the two types of degrees, the difference between Democrats and Republicans disappears,” said Paul E. Peterson, an Education Next senior editor who is also the director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. “In other words, when people have information, the partisanship that we originally identify seems to have evaporated.”

That finding is particularly noteworthy coming on the heels of the June Pew survey finding an increasing partisan divide over higher education. Two years ago, 54 percent of Republicans told Pew colleges had a positive impact on the direction of the country, according to that survey. That fell to 43 percent last year and 36 percent this year. Democrats, meanwhile, have gradually become more positive about higher education, with 72 percent this year viewing higher ed as having a positive effect, up from 65 percent in 2010.

Even so, observers on both the left and the right said the Education Next findings are interesting but not necessarily surprising.

“I’m not that surprised because we’re polling parents,” said Mark Huelsman, a senior policy analyst at the progressive think tank Demos, which has been a major advocate for free tuition in public higher education. “By and large they aspire for their children to get a four-year degree.”

More than anything, the results show that people need time to do calculations for a cost-benefit analysis, said Mary Alice McCarthy, director of the Center on Education and Skills at New America.

“People have a hard time doing math on the phone,” she said. “I wouldn’t read too much into the results.”

“The Pew survey was very much a 30,000-foot view of higher education,” said Rick Hess, resident scholar and director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. The Education Next survey, on the other hand, steered people away from thinking about their general impressions or the most recent news article about higher ed that upset them. It steered them toward considering the way educational decisions affect their families and their bank accounts over time.

“Republicans, for a host of reasons — personally, I think, most of them legitimate — have become quite skeptical about four-year institutions,” Hess said. “But when you ask them questions that point out people who go to four-year institutions are much more likely to earn a good living, that not only gives them information, but it reframes what they’re thinking about. It’s the same thing with Democrats.”

Hess is also an executive editor at Education Next. But he was not aware of the survey or involved in it, he said.

Republicans and Democrats are much more similar when they are talking about a cost evaluation — about, say a gallon of milk — than they are when they are asked what they think about higher education in general, Hess said.

“If you’re asking if $2.39 is a good price for a gallon of milk, I think you’d get similar answers right or left,” Hess said. “If you say, ‘Do you think milk should be organically farmed?’ I think you would see more right-left split.”

The Education Next survey also found that white survey respondents without a college degree were less likely than their peers with a degree to want their children to go to a four-year institution. When asked what they would want for their children but not given any cost or earning information, 57 percent of whites without four-year degrees said they would want their children to go to a four-year university. Another 30 percent said they would want their children to go to a community college.

Those findings are substantially different from those for whites with four-year college degrees, 88 percent of whom said they would want their children to go to a university for a four-year degree. Only 8 percent of whites with college degrees said they would want their children to go to a community college.

The splits between whites with and without four-year degrees were virtually unchanged after respondents were given information on both earnings and costs. In other words, those without degrees don’t seem to lack the information they need to make college and career choices, according to Education Next.

Results were similar when splitting white responses along income lines. Only 56 percent of white respondents with incomes of less than $75,000 said they would want their children to go to four-year universities, compared to 80 percent of whites with incomes of $75,000 or more. When they were given information on earnings and cost, 52 percent of the lower-income group chose four-year universities and 79 percent of the higher income group did so.

Hispanic survey respondents did show a substantial difference based on information provided, however. Without being told about the costs or benefits of college, 61 percent of Hispanic respondents said they would want their children to attend a four-year university. That jumped to 72 percent after they were told about earnings and costs.

Sample size limitations prevented pollsters from breaking out results for black non-Hispanic respondents.

Affirmative Action

The survey also contained a set of questions that is pertinent in light of reports that the Trump administration will investigate colleges and possibly sue them over affirmative action.

Respondents were asked whether professors’ racial and ethnic backgrounds, gender and political opinions “should be considered to help promote … diversity among college faculty, even if that means hiring some … professors who otherwise would not be hired” — or whether professors should be hired “solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in few” minority, female or conservative professors being hired.

Only 19 percent of respondents said racial and ethnic background should be considered, with 6 percent of Republicans agreeing and 28 percent of Democrats agreeing. Just 14 percent said gender should be considered, with 5 percent of Republicans and 21 percent of Democrats agreeing.

A quarter of respondents said political opinions should be considered, with 30 percent of Republicans agreeing and 21 percent of Democrats agreeing.

The only breakdown of the results on racial lines that was available was for Hispanic and white non-Hispanic respondents, again because of sample-size issues for black non-Hispanic respondents. Among Hispanic respondents, 33 percent said racial and ethnic background should be considered, 16 percent said gender should be considered, and 27 percent said political opinions should be considered. Among white non-Hispanic respondents, 12 percent said racial and ethnic background should be considered, 10 percent said gender should be considered, and 21 percent said political opinions should be considered.

Some commentators noted that Republicans were more likely to support such hiring policies when it would presumably lead to more hiring from their ranks. But the same could be said for Democrats.

The findings show how unpopular such hiring policies are across the spectrum, said Max Eden, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute.

“It’s interesting how it is such a strongly minority opinion against both parties that race or political ideology should be taken into account when it comes to hiring,” Eden said.